Playing with perception is a timeless phenomenon that fascinates people today just as much as it did 400 years ago. Back then, new discoveries in the field of optics and associated artistic experiments led to astonishing effects in painting.

Get to know some of the virtuoso tricks that Rembrandt and Van Hoogstraten used, sometimes in surprising combinations, to deceive observers.

However, these two painters were not the first to achieve mind-boggling artistic results by applying innovative methods. Some works from the collections of the Kunsthistorisches Museum marry well with paintings by Rembrandt and Van Hoogstraten.

Ancient Roman author Pliny tells the story of a competition between the painters Zeuxis and Parrhasius. Zeuxis is said to have portrayed grapes so true to life that they attracted hungry birds. Confident of victory, he then invited Parrhasius to pull aside the curtain in front of the latter’s own painting so that he could look at the picture behind it. But the curtain itself was merely painted! So, Parrhasius took the victory as he had managed to fool even his fellow artist.

Reference is made to this story again and again in art, including by Rembrandt.

From the 1640s onwards, he began to experiment with tricks of the eye, using the motif of the curtain as a connecting element between the space inside and the space in front of the picture. Rembrandt’s pupils also played with this boundary in many of their works.

2

Rembrandt, A Woman in Bed (Sarah Awaiting Tobias), 1647, National Galleries of Scotland. Presented by William McEwan 1892 © National Galleries of Scotland, photo: Antonia Reeve

2

Rembrandt van Rijn, A Woman in Bed (Sarah Awaiting Tobias), 1647, National Galleries of Scotland. Presented by William McEwan 1892 © National Galleries of Scotland, photo: Antonia Reeve

Outside the box?

Breaking boundaries

‘Jan van Eyck made and completed me’

Jan van Eyck on a picture frame (1439)

As early as the fifteenth century, a kind of visual revolution occurred in the field of artistic deception.

In northern Europe, the Early Netherlandish painter Jan Van Eyck led the way. Through close observation and use of the still young technique of oil painting, he achieved an unprecedented realism in his paintings. What was also new was that he sometimes included the painted frame in the picture narrative in the form of hidden messages. By blurring the boundary between frame and image, he tempted observers to ‘grasp’ what they were seeing.

3

Jan van Eyck, The goldsmith Jan de Leeuw, dated 1436 © KHM-Museumsverband, Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien

4

Rembrandt van Rijn, Girl in a Picture Frame, 1641.© The Royal Castle in Warsaw – Museum

Some 200 years later, Rembrandt went a step further:

The person portrayed appears to reach over the frame of the picture. Rembrandt skilfully made the boundary between the real and painted picture frames disappear. The picture was probably discussed intensively in his workshop and copied several times.

Full vista?

Looking in and looking out

‘First of all, on the surface on which I am going to paint, I draw a rectangle of whatever size I want, which I regard as an open window through which the subject to be painted is seen.’

Leon Battista Alberti, 1435

Jacobus Vrel, Woman at the Window 5

With his Doorkijkjes (vistas), Van Hoogstraten created fantastic views into rooms or landscapes. He preferred to use thresholds between inside and outside in the form of window or door openings of real proportions, as seen here exposing the rooms inside a typical Dutch house of the time.

With this approach, Van Hoogstraten built on insights relating to perspective that artists of the Renaissance began to use around 200 years earlier in the fifteenth century.

Those insights helped them open up the depth of the pictorial space convincingly. Alongside a fictitious expansion of the space to create depth, the apparent movement out of the image also played a significant role. By depicting fleeting moments, such as a glance out of a window, artists succeeded in arousing the curiosity of the observer. A master in this field was Gerard Dou, likewise one of Rembrandt’s pupils.

5

Jacobus Vrel, Woman at the Window, dated 1654 © KHM-Museumsverband, Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien

6

Samuel van Hoogstraten, The Slippers, 1650/75, Paris, Musée du Louvre; photograph © RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre) / Michel Urtado

7

Gerard Dou, Old woman at the window, watering flowers , 1660/65 © KHM-Museumsverband, Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien

The Italian painter Parmigianino caused a sensation at the beginning of the sixteenth century with a small but particularly refined object. His exploration of reality and perception resulted in a completely new self-portrait, which appears to show him in a convex mirror, breaking out of the confines of the two-dimensional picture.

8

Francesco Mazzola, gen. Parmigianino, Self-portrait in a convex mirror, 1523/24

© KHM-Museumsverband, Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien

More than 100 years later, Rembrandt and Van Hoogstraten go even further in playing with deception in their illusionistic objects.

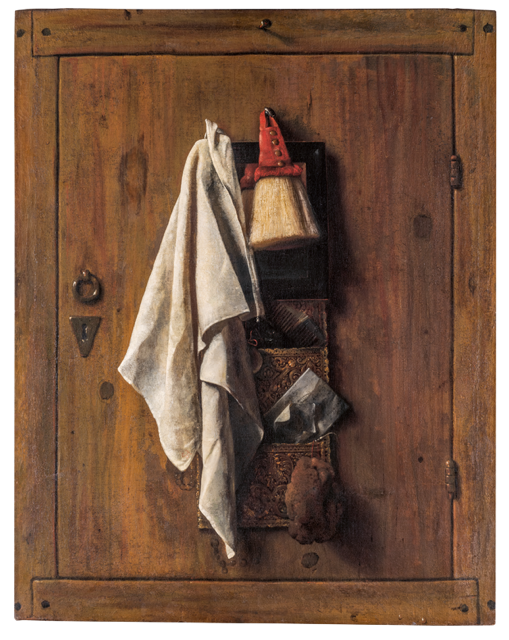

They completely dispense with conventional frames and take into account the planned location of the picture. For example, Van Hoogstraten’s wooden cupboard door with objects hanging from it might have been presented recessed in a wall panel.

8

Samuel van Hoogstraten, Trompe-l’oeil Still Life, 1655, Academy of Fine Arts Vienna © Picture Gallery of the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna

Enlightenment?

The colours of light

‘(...) likewise, the rays of light, when they meet a body that does not allow them to pass through, must also be cast back.’

René Descartes, 1664

Another important ingredient of illusionistic painting is light.

Through a strong contrast between light and dark, Rembrandt succeeded, even early on, in increasing the drama of his pictures and elevating the presence of his subjects. In this picture, light gives the white dress such intensity that, like light reflected in a mirror, it makes other surfaces shine too. Van Hoogstraten tried to underpin his teacher’s insights with theory and methodically investigated the effects of different light sources and their influence on colour.

Around the same time, his famous colleague Vermeer used new insights into optics to lend his works a special atmosphere. He left his painting TheArt of Painting as an impressive testimony to his ability to fool observers.

9

Rembrandt van Rijn, Judith at the Banquet of Holofernes, 1634, Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado

© Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid

10

Johannes Vermeer van Delft, The art of painting, 1666/68

© KHM-Museumsverband, Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien

At your fingertips!

Custom-made picture puzzles

‘A perfect painting is like a mirror of nature; it makes things that are not there appear to exist and deceives in a permissible, pleasurable, and praiseworthy way.’

Samuel van Hoogstraten, 1678

His preoccupation with the theme of illusion repeatedly led Van Hoogstraten to come up with new pictorial ideas. His painted ‘pinboards’ became a runaway success

In them, he depicted life-size everyday objects and personal items deceptively realistically and all held in place by straps. In this way, these things that are distributed across the surface seemingly randomly appeal not only to the sense of sight but also the sense of touch. Such paintings are also referred to as trompe l’oeil (trick of the eye) still lifes and were extraordinarily popular in the seventeenth century. On this particular ‘pinboard’, Van Hoogstraten has collected 21 items. Many of them relate to his work not only as a painter, but also as a writer and art theoretician.

You can learn more about some of the objects, a few of them puzzling, directly in the picture – and discover similar objects from the

Kunsthistorisches Museum!

While the items under the upper strap of the pinboard are primarily writing utensils, the lower strap mainly holds cosmetic articles. These include a shaving brush and a razor, probably with a tortoiseshell handle.

This gold medallion shows Emperor Ferdinand III in profile. Van Hoogstraten received it, along with a gold chain of honour, during his audience at the imperial court in 1651 as an expression of the emperor’s admiration for the painter’s exceptional illusionistic abilities. It became his trademark and spoke of recognition and affluence.

This poem, which Emperor Ferdinand III had written by Johann Wilhelm von Stubenberg in praise of Van Hoogstraten to celebrate his art, refers to the anecdote of the competition between the Ancient Greek painters Zeuxis and Parrhasius: Van Hoogstraten apparently even surpassed both of them by fooling the emperor with his painting.

You who doubt that the masterly hand of Zeuxis,

which fooled birds with false painted grapes,

could be robbed of its mastery by a nobler hand

through a fine brush and white picture canvas,

come look at Van Hoogstraten! Through the art of his brush, the Ruler of the whole world

has likewise been deceived.

J. W. von Stubenberg

Vienna 16[…]

Such oval turned ivory boxes usually contained small portraits as souvenirs and collectibles. Behind this container is a slightly opened document with loosened sealing straps. But neither the box nor the document betrays the secret of its contents.

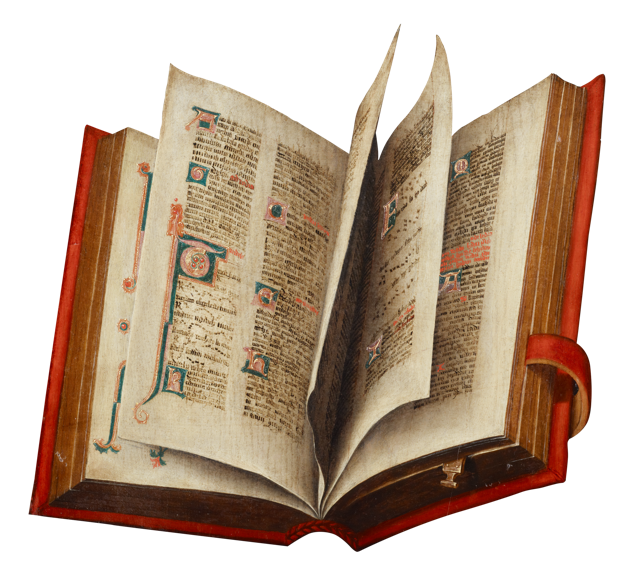

The golden lettering on the book with the red leather cover reveals that it was written by Van Hoogstraten himself. The tragedy ‘Dierijk en Dorothé’ was published in The Hague in 1666; it tells the story of the siege of Dordrecht in the middle of the eleventh century, complemented by the love story between Dorothé, the daughter of the mayor, as the personification of Dordrecht and Count Dirk IV of Holland. Van Hoogstraten also links the story to references to contemporary political happenings in his home city of Dordrecht.

Several of the objects provide clues to Van Hoogstraten’s output as a writer. The two booklets behind the lower strap reveal just a few letters. These suggest that they are copies of Van Hoogstraten’s tragedy ‘De Roomsche Paulina’, which was published in The Hague in 1660. In this classical Roman tragedy, Paulina, the wife of a distinguished Roman, loses her chastity through intrigue and then avenges this betrayal.

The quill and knife, like the paper scissors and rolled paper, refer to Van Hoogstraten’s work as a writer. The rolled-up booklet at the top left has a marbled cover. The technique of marbling came to Europe at the end of the sixteenth century via the Ottoman Empire and was mainly used as special decoration in the book trade. In a kind of illusionistic game, Van Hoogstraten finally transfers the skilfully imitated material to the medium of painting.

In the lower part of the pinboard there are two combs: a smaller double comb with fine teeth, of the kind still used today to remove lice, and a coarse comb, presumably made of horn, for wigs for example. They might also symbolise the ordering of thoughts.

On a silk ribbon hangs an oval pendant framed by gemstones set in gold. The relief cut into stone presumably shows the profile head of an Ancient Roman emperor.

This precious piece of jewellery could be an allusion to the fact that Ferdinand III was one of Van Hoogstraten’s admirers. As Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, he saw himself as a successor to the ancient rulers.

An opened sealed letter has been placed in front of the described sheet of paper. The letters on the seal refer to the artist’s name: Samuel van Hoogstraten. Alongside this is a stick of sealing wax, possibly alluding to Van Hoogstraten’s work as a writer. The glasses, as a symbol of the sense of sight, might point to his industry as a painter.

Hoogstraten, Feigned Letter-Rack Painting , 1666/78, Staatliche Kunsthalle Karlsruhe

MyPinboard

An interactive station in the exhibition

To this day, artists continue to use new technical discoveries to astonish their audience. Although sensory illusions are more present than ever in this age of digital image processing and virtual reality, the enthusiasm for illusionistic manifestations is unabated.

However, the things that accompany us through our daily lives, or which are regarded as status symbols, look very different today from how they did 400 years ago.

That is why we invite you to put together your own personal ‘pinboard’ in the exhibition. The objects you can select for this have been created by a program that specializes in producing ‘artworks’ using artificial intelligence. So, with the help of new technology, you can compete virtually with Rembrandt and Van Hoogstraten. Some of the results that may encourage reflection on the future development of illusionistic art can be seen here!