The pupil and his teacher …

Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn and his pupil Samuel van Hoogstraten were masters at applying colour, perspective, and illusionistic techniques.

But who were the men behind these big names in the art world?

Rembrandt

Harmenszoon van Rijn

(1606–1669)

From pupil to teacher

In 1622, Rembrandt decided to train as a painter and began an apprenticeship with Jacob Isaacsz van Swanenburgh in Leiden. Moving to Amsterdam in 1624, he spent six months at Pieter Lastman’s workshop before setting up his own studio in Leiden.

From 1634, Rembrandt himself trained young artists in his studio in Amsterdam. Today, some 50 artists are associated with Rembrandt’s workshop, 20 of them are documented and 30 are connected to the master through their style of painting and way of working. If Rembrandt ever kept records of his pupils, these have been lost. For many of these painters, he would have been their second teacher following an apprenticeship completed elsewhere. The young painters probably used Rembrandt’s training, his popularity, and his contacts as a springboard for their own careers.

1

Rembrandt van Rijn, Self-Portrait with Two Circles, c.1665,

English Heritage, The Iveagh Bequest (Kenwood, London) © English Heritage

2

Rembrandt van Rijn, Saskia van Uylenburgh in Arcadian Costume, 1635, London, The National Gallery; bought with contributions from the Art Fund, 1938 © The National Gallery, London

1634

In 1634, Rembrandt married Saskia van Uylenburgh, the niece of Rembrandt’s colleague Hendrik van Uylenburgh. The couple’s first three children died only a few weeks after they were born. Saskia passed away in 1642, shortly after giving birth to their son Titus. Rembrandt depicts his wife in numerous paintings, etchings, and drawings.

1642

It is likely that Geertje Dircks joined the family household around 1642 as a nanny for Titus. She was born between 1600 and 1610, making her a similar age to Rembrandt, and also widowed. Geertje lived with Rembrandt and Titus for about six years in total, during which time a romance developed between her and the painter. After they separated in 1649, Geertje sued Rembrandt for a yearly maintenance allowance. She won the case, and Rembrandt was ordered to pay her 200 guilders a year.

1649

In 1649, Hendrickje Stoffels came to Rembrandt as a maid; she may well have been the reason for the separation between the painter and Geertje Dircks. Hendrickje was twenty years younger than the painter and had been forced into domestic service by her mother. Their illegitimate daughter Cornelia came into the world in 1654. She too was used by Rembrandt as a model in many of his works.

Rembrandt’s ‘dream house’

On 3 January 1639, Rembrandt signed the contract to purchase the house on Sint Antoniesbreestraat, for which he paid 13,000 guilders. The house was big for an Amsterdam artist, and it is likely that Rembrandt chose it to make an impression on potential clients.

approx. 1,806,000 €

or approximately 43 annual salaries of an average earning worker at the same time

Back then, a craftsman earned around 300 guilders a year.

Today, the average income is € 42,000.

Source: Rembrandthuis

Many of the rooms were used for artistic endeavours and the training of pupils. There were two studios, a large one for Rembrandt and a smaller one for his pupils. The house probably also contained a printing workshop as well as private rooms on the second floor, and he used the gallery to work on large paintings such as the Night Watch.

Rembrandt’s art collection was also kept in the house. In 1659, his collection of ‘paper art, rarities, antiques, medals, marine life, and plants’ was valued at 11,000 guilders and his collection of paintings was valued at 6,400 guilders.

3

Museum Rembrandthuis, Foto/Photo: Aad Hoogendoorn © Rembrandthuis, Amsterdam

Son and art dealer

Born on 22 September 1641, Titus van Rijn was the only one of Rembrandt’s four children by his first wife, Saskia, to reach adulthood.

The painter trained his own son himself, but Titus’ painting ability was limited and he eventually worked as an art dealer and manager of his father’s assets.

Rembrandt lived beyond his means – he used his decidedly high income not to repay his home loan but rather to expand his own art collection. His financial situation worsened at the end of 1655, and he tried at first to gain money by selling his collection at auctions. In 1656, the artist was ultimately declared insolvent and everything he owned was inventoried and sold. Titus and Hendrickje Stoffels finally established an art dealership together, they hired Rembrandt as an employee and, in so doing, they secured new business contacts and commissions for the painter.

4

Rembrandt van Rijn, Titus van Rijn, the Artist’s Son, Reading, c.1658, Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna, Picture Gallery © KHM-Museumsverband, Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna

Out into the world from Rembrandt’s workshop

Samuel van Hoogstraten came to Amsterdam and to Rembrandt’s workshop in 1642 as a 15-year-old, having already been trained in Dordrecht by his father, the painter and silversmith Dirck van Hoogstraten. He was joined in the workshop in the 1640s by fellow pupils Abraham Funerius and Carel Fabritius.

A painting apprenticeship typically lasted between four and six years. The pupils learnt basic technical skills, such as how to mix paint and to cover and prime canvases. The first step involved in an artistic education was to copy paintings and prints, after which apprentices moved on to drawing and painting objects, before finally learning how to paint live models.

Preserved drawings provide an insight into the techniques and content of the teaching in Rembrandt’s workshop. They reveal group sessions in which all the artists drew the same model. There are drawings by Van Hoogstraten and Fabritius depicting the same model from slightly different angles.

Hoogstraten, Der innere Burgplatz in Wien 6

‘This is the first painter

to have fooled me.’

A star in Vienna

In 1651, Van Hoogstraten travelled to Vienna and was granted an audience with Emperor Ferdinand III in August.

He presented the ruler with three paintings: a portrait of a gentleman, a depiction of Christ crowned with thorns, and an illusionistic pinboard. According to the report on the encounter, Ferdinand took a liking to the first two pictures, but was absolutely captivated by the last one.

His reaction was: ‘This is the first painter to have fooled me.’ The emperor honoured Van Hoogstraten by awarding him a portrait medallion.

Ferdinand III had been extremely highly educated and trained by the Jesuits in Vienna. He is described as pious and well educated in philosophy and other sciences. The emperor had a special interest in music, composing pieces himself, which were appraised by his court music director, Giovanni Valentini. He also supplemented the imperial collections with paintings by famous Renaissance and Baroque painters, such as Titian, Tintoretto, and Rubens.

London Calling

Following his journey through Central Europe and Italy from 1651 to 1655 and a longer stay in his home city of Dordrecht, Van Hoogstraten lived in London with his wife Sara Balen from 1662 to 1667.

His time in England was dominated by portrait commissions and the motif of architectural and perspective views newly developed by Van Hoogstraten. These are ‘doorkijkjes’ (vistas), which open up endless views into other rooms and landscapes.

It is likely that Van Hoogstraten based the buildings and palaces he portrayed on Mediterranean examples he had seen on his journey through Italy, without painting actual buildings. The rooms inside the ‘vistas’, on the other hand, are reminiscent of Dutch interiors. The ever increasing size of the architectural views is extraordinary. Van Hoogstraten offers observers even life-size thresholds to look through that invite close examination.

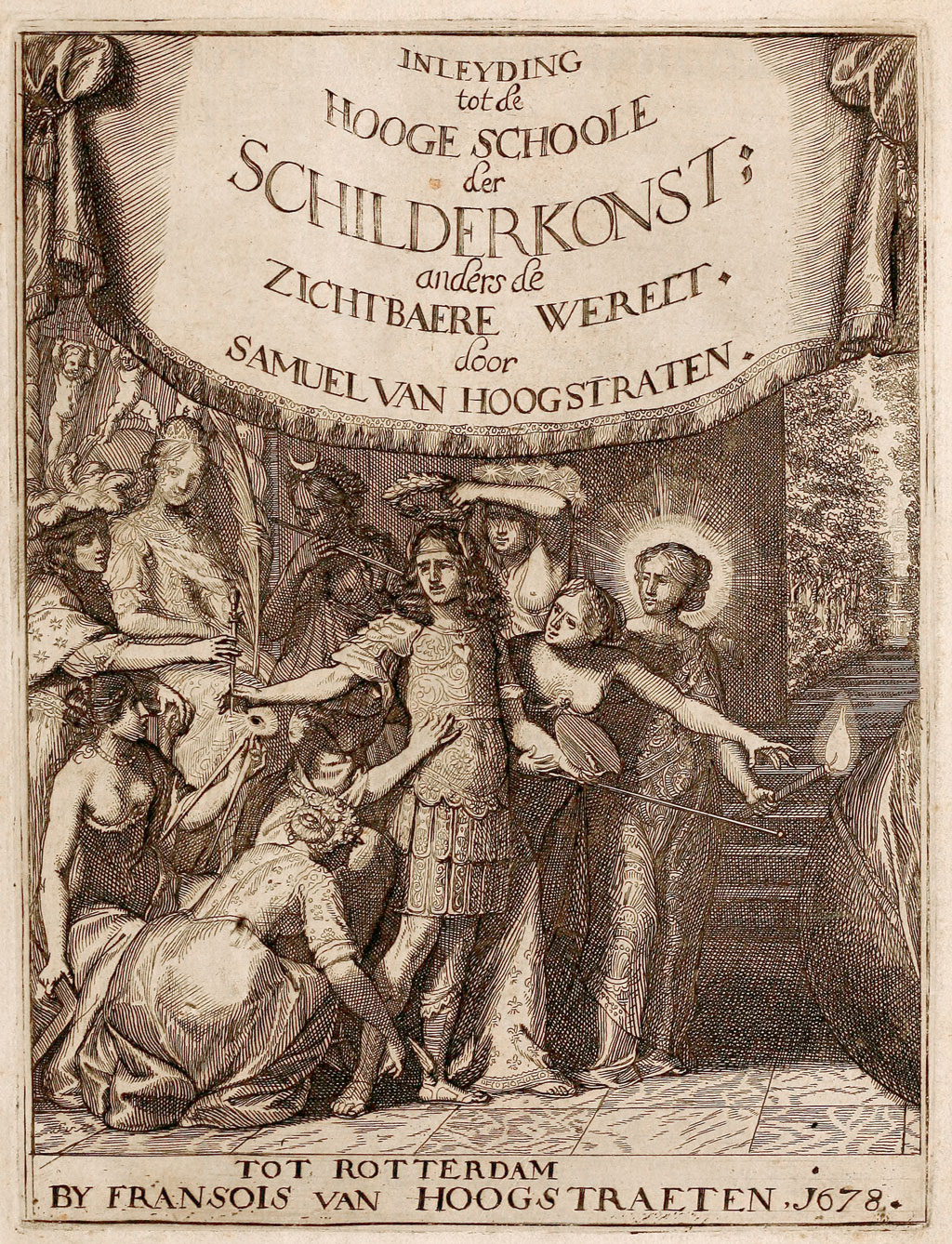

The visible world

From around 1675, Van Hoogstraten began working on his treatise on painting, Inleyding tot de hooge schoole der schilderkonst, anders de zichtbaere werelt (Introduction to the Academy of Painting; or, The Visible World), which was finally published in 1678, the year of his death.

The aim of the treatise was to elevate the prestige and status of painting, which at that time was understood more as a craft or common art. It was aimed at painters, pupils, and connoisseurs.

In this, Van Hoogstraten defined painting as ‘a science for depicting all the ideas or concepts that the entire visible world can provide and deceiving the eye with outline and colour.’ This transforms painting into a universal science that portrays all that the eye can see and, at the same time, deceives the eye. In addition, he also repeatedly offers insights into his time in Rembrandt’s workshop and devotes himself to practical topics, such as colour, painting styles, and the appropriate place for installing paintings.

5

Samuel van Hoogstraten, Self-Portrait, 1645, LIECHTENSTEIN. The Princely Collections, Vaduz–Vienna © LIECHTENSTEIN. The Princely Collections, Vaduz–Vienna

5

Samuel van Hoogstraten, Self-Portrait, 1645, LIECHTENSTEIN. The Princely Collections, Vaduz–Vienna © LIECHTENSTEIN. The Princely Collections, Vaduz–Vienna

6

Jan van den Hoecke, Portrait of Emperor Ferdinand III, c.1643, Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna, Picture Gallery © KHM-Museumsverband, Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna

7

Samuel van Hoogstraten, Perspective View with a Young Man Reading in a Renaissance Palace, 1662/67, Dordrechts Museum © Dordrechts Museum, photograph: Bob Strik, Reprorek

8

Frontispiece from: Inleyding tot de hooge schoole der schilderkonst; anders de zichtbaere werelt (Introduction to the Academy of Painting; or, The Visible World), 1678, Amsterdam, Rembrandt House Museum © Rembrandt House Museum, Amsterdam. Photograph: Anne Roos